For as long as I can remember, this hairbrush, mirror, and lace doily have lived on the bedroom dresser in my grandparents’ bedroom. I remember playing with them as a little girl – marveling at how something as simple as a hairbrush could be made ornate. I don’t recall my grandmother ever using them. But I knew they were hers. I associated them with her. And they belonged on my grandparents’ bedroom dresser, next to the framed photo of my whole family at my bat mitzvah, and facing the large painted portraits of my mom and my two uncles when they were children, hanging on the wall over my grandparents’ bed.

I don’t know what I will do with the hairbrush and the mirror, but I couldn’t bear the thought of letting them go. As if leaving them in the donation box meant giving away the part of me was who believed everything my grandmother touched was beautiful because she had touched it. I added them to my pile on the bed in my mom’s childhood bedroom, along with two of grandmother’s paintings, a couple of photo albums, and a needlepoint she made. I remember looking at the needlepoint as I fell asleep while my grandmother sang Brahms lullaby in Yiddish.

The hairbrush and mirror look out of place next to these handmade treasures, and next to the menorah – the metal dark with age – that my mom and her brothers grew up lighting for Chanukah. We lit that menorah together with my grandfather during our visit and I am so glad we were there to do that. I am so glad Ella repeated the words after me, while my grandfather beamed beside her. I never expected that I’d be taking this menorah – or the paintings or needlepoint or the hairbrush and mirror – home with me, just over a week later.

I went to my grandfather’s CD tower and pulled out an album from clarinetist, Acker Bilk. When I picked up the clarinet in band in fifth grade, my grandfather introduced me to his “Stranger on the Shore,” and we loved to listen to it together – plaintive, longing, wistful. He and I were supposed to dance to that song at my wedding but my grandmother was tired and needed to get home before the DJ got around to playing it. Now the song was echoing in my heart as I walked through my grandparents’ house – full of things, but empty of them.

My grandparents’ house was our second home when I was growing up. They only lived about 25 minutes from us, and we were there every Sunday for dinner. After I left for college, every time I came home to visit my parents, we also had Sunday dinner with my grandparents. My mom dutifully shared photos of each Sunday meal in our family group chat, so I felt connected to those gatherings even when I lived far away. As a child, I didn’t realize how rare it was to have no true “extended” family, because there were no extensions – we saw each other every week, so everyone was immediate. Everything was always. My grandparents’ house was the other home I came home to, even after my grandmother died in 2015. We all still miss her, but I loved that I could feel her comforting presence so strongly when I visited. Everything she touched, like the brush and the mirror, was right where she left it.

I said goodbye to my own childhood home three times, but when I left after winter break, I was not prepared to say goodbye to this one. My parents were supposed to move away and sell the house over the summer, so I visited and said goodbye to their house in May, walking through it with my phone, taking photos and videos. I narrated favorite memories associated with every corner, floorboard, and cabinet. My parents ended up pushing the move back, and I was grateful to have one more Thanksgiving and winter break in the house.

Joseph, Ella, and I were in Southern California, visiting our homes, and our families in them, from December 20th-December 28th this year. We spent time with my grandfather on 21st and 25th. My grandfather had just received a good report from his primary care physician. At the age of 95, he still lived independently and read voraciously. Driven by lifelong intellectual curiosity and a zest for learning, my grandfather led three discussion groups in his 90s, for other octo and nonagenarians. When I was in college, my Grampie was the only person besides my thesis advisor to have read my entire undergraduate senior thesis – which was a serious undertaking, because that thing was over 100 pages on the American Revolution. I remember when he handed it back to me – with typos marked in red! Typos my thesis advisor herself had missed. I was so touched that he’d read the whole thing and with such attention to detail. He also read my masters thesis, and, I believe, most, if not all, of my rabbinic capstone.

In the living room of their house, the book my grandparents made for me, of all the poetry I wrote between the ages of 6 and 13, was at the center of their coffee table. They called it “Voyage of the Imagination,” and they had presented it to me for my bat mitzvah. It’s one of the most cherished gifts I’ve ever received – not just the book itself, but their relentless belief in my words, in my story, and in me. My grandfather believed I had something to say, something precious to offer – and whether it was an elementary poem in rhyming couplets, an academic thesis, or a high holiday drash, he wanted to hear it, read it, mark it up with a red pen and hand it back to me with one thousand questions. Grampie’s great-granddaughters – who called him “Double,” for double-grandparent – were the light of his life, and having Ella there to visit, chatting, playing, and singing, clearly made his whole month. I had no reason to think it was the last time. But I guess no one ever really does.

The day we flew back to Illinois, my grandfather wasn’t doing well. He’d had a couple of on and off health issues in the last year – but he was in his 90s, and that happens. A nagging feeling tugged at my heart but I shrugged it off. My grandfather had bounced back so many times that we barely worried. He went into the hospital and my mom kept us updated on his progress. My mom told me that Grampie had decided that if he wasn’t getting better, he was at peace and ready to join my grandmother. This was his decision. I was sure he would recover.

On December 31st, I woke up feeling nauseous. I assumed it was nothing and went to work. Then my mom messaged me. My grandfather was on hospice. Not long after that, he was gone, and I discovered I had food poisoning. I went home to look at flights. The funeral would be on January 2nd, and I would be officiating.

I wrote the eulogy in the airport on January 1st. My grandfather had been an aviation pioneer – involved in the early years of commercial air travel – and even as I sat there, queasy and grieving, it felt like an appropriate place to write something beautiful for him. And I did write something beautiful. I wrote a beautiful eulogy and designed a beautiful funeral. I officiated a beautiful service on January 2nd, after spending the night awake and writhing with stomach pain. It was an honor to his memory and a love letter to his legacy. I didn’t cry until I was in my grandparents’ house for the last time, realizing that these things – from the hairbrush to the Sunday dinner table – would no longer be there, waiting for me to come home to them.

I know that a table isn’t the people who sat around that table together, but my memories are wrapped around the table legs. My memories are laughing with my grandfather in the living room, falling asleep to my grandmother’s voice, running their fingers over her hairbrush. My memories’ hands are sweaty and struggling to turn the doorknob of my parents’ house after high school cross-country practice. They are tucking a letter for the tooth fairy under the pillow in my childhood bedroom – after I swallowed my first tooth, I wrote the letter asking the tooth fairy if I could have the prize anyway (she conceded). My memories are following baby Ella as she crawls down the hallway toward the den. My memories are sharing an indoor picnic in that den, sitting on a blanket in front of the fireplace and listening to the rain fall outside. My rituals of return brought me back to the same two homes my entire life. I miss my grandparents. I will miss these places too. It feels like my childhood and young adulthood chapters are closing as my family tries to close these two houses.

But thankfully, memories cannot be sold. Thankfully, I am a ritual artist, and we are creating new ones. Ella FaceTimes with my parents each morning. It’s not Sunday dinner, but it is meaningful. My parents are moving, but their new home will become the house Ella remembers. My grandfather died, but I think of him when I listen to “Stranger on the Shore,” and when I ask too many questions. My grandmother is gone, but I hear her voice when Ella listens to Brahms Lullaby as she falls asleep.

The goodbyes pile up in the inbox of my heart, and I can only mark “unread” for so long before I need to respond. So, here I am, in a coffee shop in Central Illinois, writing back – to my grandparents, to my houses, and to the parts of me that still live there. More goodbyes are needed, but I only have capacity to respond to a few at a time, and I am starting with these. “I am sorry for the delayed response, beloveds. I promise I haven’t forgotten. I promise I will always remember.”

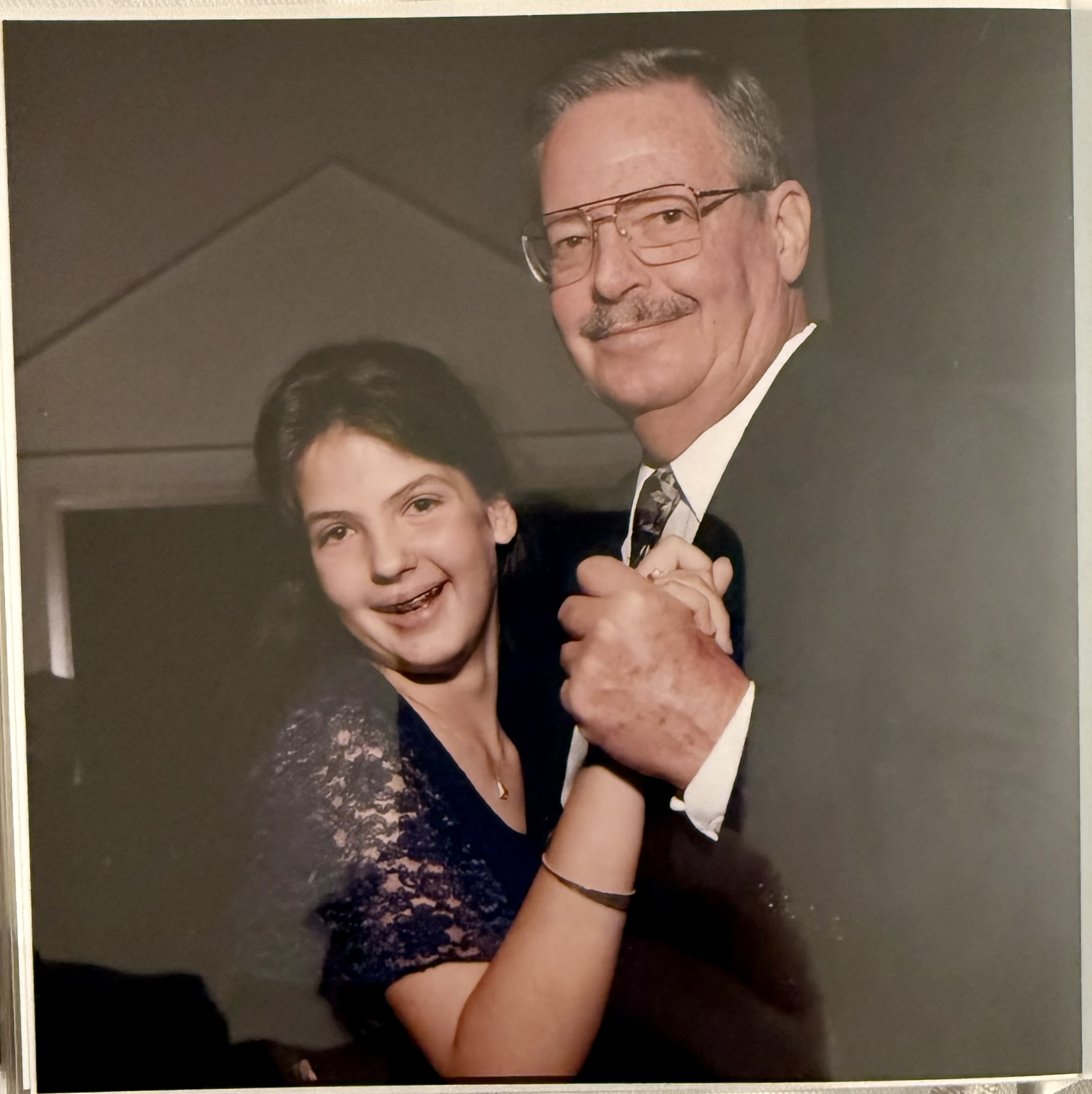

Three of these photos are from my Bat Mitzvah (Dec. 7, 1996). One of these photos was taken not long after I was born (Dec. 1983) on the couch in my grandparents’ house. All of these photos were in an album at my grandparents’ house, along with many other cherished memories. May theirs always be for blessing.

Berlin taught me a lot about looking back. For the first time, I had the opportunity to ask non-Jewish Germans, outright: What did your family do in the war? Most of them had no idea. It wasn’t something you talked about, their families said. It was something you remembered. You can’t walk anywhere in Berlin without remembering something. The city itself seems to have PTSD. Look down at the cobbled sidewalks and you see gold stumbling stones inscribed with the name of a Jew who lived in that spot, noting the date of deportation and the place of their death. Look up and there’s the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, tremendous and dominating, so much a part of the landscape that children have snowball fights amid the giant blocks during the winter. Turn the corner and there’s another memorial, in Hebrew, English, and German. Everywhere, the memory of someone we lost and the culture that went with them.

Berlin taught me a lot about looking back. For the first time, I had the opportunity to ask non-Jewish Germans, outright: What did your family do in the war? Most of them had no idea. It wasn’t something you talked about, their families said. It was something you remembered. You can’t walk anywhere in Berlin without remembering something. The city itself seems to have PTSD. Look down at the cobbled sidewalks and you see gold stumbling stones inscribed with the name of a Jew who lived in that spot, noting the date of deportation and the place of their death. Look up and there’s the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, tremendous and dominating, so much a part of the landscape that children have snowball fights amid the giant blocks during the winter. Turn the corner and there’s another memorial, in Hebrew, English, and German. Everywhere, the memory of someone we lost and the culture that went with them.

tury, and part of our collective Jewish memory. I know that some are not yet ready to get on a plane and fly to Berlin to cope with it. But I wonder if each of you can take this opportunity over the next ten Days of Awe to consider other evaded issues in your personal experience. What other traumas have you been ignoring? What is it that you are remembering, but not facing? What would it be like for you to engage directly with a painful experience in your personal memory – perhaps the death of a loved one, a challenge to your identity, a moment when you were unkind to someone who reminded you of something you fear in yourself? Can you acknowledge your failings and traumas without allowing them to consume you?

tury, and part of our collective Jewish memory. I know that some are not yet ready to get on a plane and fly to Berlin to cope with it. But I wonder if each of you can take this opportunity over the next ten Days of Awe to consider other evaded issues in your personal experience. What other traumas have you been ignoring? What is it that you are remembering, but not facing? What would it be like for you to engage directly with a painful experience in your personal memory – perhaps the death of a loved one, a challenge to your identity, a moment when you were unkind to someone who reminded you of something you fear in yourself? Can you acknowledge your failings and traumas without allowing them to consume you?